Mexico 2025: Generous AI Promises, Few Finished Products

STORY INLINE POST

As the old saying goes, promises cost nothing. And the Mexican government has been generous with promises about artificial intelligence: national laboratories, sovereign language models, supercomputers with Aztec names, public AI schools. What's scarce are finished products. As of December 2025, the inventory of what actually works fits on a napkin.

2025 was a fertile year for announcements. In April, President Claudia Sheinbaum promised the National Artificial Intelligence Laboratory "by October." October came and went, the laboratory didn't. In July, Marcelo Ebrard announced a homegrown language model; in November he presented "KAL," with no technical documentation, no code, no benchmarks. Also in November came Coatlicue, the supercomputer that will be "the most powerful in Latin America" — when it's built, in 2026, if all goes well. The Public AI Training Center opened applications, but classes start in January 2026. The National AI Policy is "in development." The AI Law has multiple initiatives in Congress, none approved.

The pattern is recognizable to anyone following Mexican technology policy: announce with fanfare, postpone quietly, and eventually a newer, shinier announcement displaces the previous one. The delivery date is always in the future. The future never arrives.

What actually works? Researchers from CIDE went looking. They found 119 AI applications reported across all three levels of government. The problem: opacity was widespread, many agencies didn't even respond, and 223 supposed "AI" applications didn't qualify as such under any reasonable technical definition. In the Mexican government, even the concept of artificial intelligence is confused. If we can't define what AI is, we can hardly implement it.

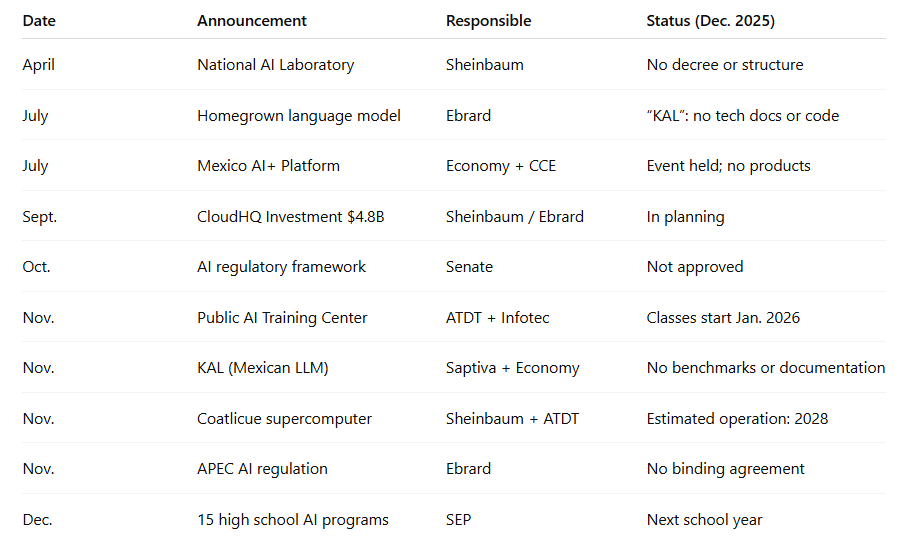

To grasp the gap between announcement and reality, just review the 2025 timeline:

Ten major announcements in one year. Zero finished products operating at scale.

What about what supposedly already works? The inventory is disappointing. MARCia, the Mexican Patent Office's search tool, has existed for years, but intellectual property professionals who use it daily prefer to avoid it — results are inconsistent and the interface impractical. Sor Juana, the Supreme Court's chatbot, was an experiment limited to a single judge's office, with results the tool itself warned could be inaccurate. The Mexican Social Security Institute has a chatbot pilot for pediatric oncology — valuable in its niche, but invisible at national scale. None of this transforms public administration. These are isolated, experimental projects with no continuity or resources to scale. More proofs of concept than public policy.

While Mexico accumulates announcements, other countries execute. The United States, on its first day under a new administration, announced Stargate: US$500 billion in AI infrastructure with data centers already under construction in Texas. But more revealing than the big numbers is the mundane: in April, the White House issued two memoranda allowing federal agencies to contract AI technology from external providers, removing bureaucratic barriers that prevented adoption. No national laboratories, no sovereign language models, no supercomputers with Aztec names. Just a clear order: you can buy AI, do it. Sometimes the most effective public policy removes obstacles rather than creating new institutions.

The contrast is instructive. Mexico bets on grandiloquence: build from scratch, technological sovereignty, names evoking the pre-Hispanic past. The United States bets on pragmatism: let institutions use what already exists. One approach generates press releases, the other generates implementations.

The irony is that those who need AI most can't use it. Judges in administrative tribunals and the federal judiciary describe backlogs years in the making. Accumulated case files, manual calculations, processes that could be automated but are still done by hand. When someone proposes something as basic as jurimetrics — using AI for deadline calculations, damage quantification, statistical projections — the reception is mixed: genuine interest from some, institutional distrust from others, and zero infrastructure to implement it. The problem isn't willingness, it's that nobody has given them the tools.

And the context makes the irony more bitter. In November 2025, federal judges were asking colleagues to chip in to buy paper and print rulings. In Monterrey, judicial workers were buying paper with their own money. Printers have been broken for months. No toner, no spare parts, no budget. Hard to talk about artificial intelligence when the judicial system can't guarantee basic office supplies.

The problem with Mexico's AI strategy isn't lack of vision, it's the excess of it. There's no shortage of Aztec names, national laboratories, sovereign language models, and promised supercomputers. What's missing are finished products, working implementations, and tools in the hands of those who need them. While other countries remove obstacles so their institutions can adopt technology, Mexico keeps inaugurating initiatives that will live and die in a press release.

Promises cost nothing, says the proverb. But they don't build infrastructure either.