Inclusive Mobility Means Democratizing Access for Everyone

STORY INLINE POST

Going to work, to school, to the doctor, shopping, meeting up with family or friends — these are all simple daily trips that are not accessible to everyone.

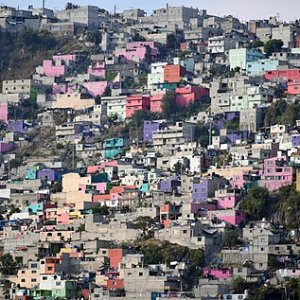

Today, not only are mobility opportunities unevenly distributed, but the potential for mobility, whether for access to employment or the organization of daily life, is not the same for all citizens. For vulnerable populations, everything is further away, more expensive, and slower. Their low income reduces their capacity for mobility. And like a vicious circle, these challenges in turn contribute to keeping them in their precarious position.

First of all, let’s be clear: private cars cannot be part of any inclusive solution as, at least in Latin America, only a minority can afford them (and in developed countries, their use should be decreased to lower carbon emissions).

Various socio-demographic criteria need to be considered to study inclusive mobility:

-

Ability: physical accessibility for disabled people

-

Age: school and hospital accessibility for young and senior people

-

Education and income: work accessibility for people who are less educated and have a lower income

-

Geography: shops, basic healthcare services, educational institutions, or services for the elderly or children should be accessible to people living in rural areas and low-density regions

We can mention a few examples to illustrate the requirement for inclusive mobility development in Mexico:

-

According to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), there are 7,168,000 people with disabilities, a number that represents 5.69% of the total population. Despite this, it was not until two years ago that the constitutional reform for the free movement of people was published in the Official Gazette, which states that "Everyone has the right to mobility in conditions of road safety, accessibility, efficiency, sustainability, inclusion, and equality."

-

In the metropolitan area of Mexico City, the few employment opportunities force more than 6 million residents from the State of Mexico to travel daily to the capital. On average, these workers spend four to six hours per day on public transportation.

-

According to a study from UNAM on mobility for older people, adults in this age group prefer to use the Metro or the Light Rail to travel across the capital; however, not all the population have access to these public transportation systems, especially those who live on the outskirts of the city.

The obstacles to mobility are economic, material, social, psychosocial, organizational, and geographical. Achieving the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) depends directly on inclusive mobility for all, with no barriers for anyone. The right to transport is defined as access to public transport, while the right to mobility is defined as access to daily activities. These rights condition most other socio-economic rights (to food, work, healthcare, education, culture, social and political life — all directly linked to the UN SDGs).

Let's follow the customer journey of a public transport user to try to understand the possible difficulties and opportunities:

I'm at home and need to go to a certain address. First, I have to look for information. I hope to find information about how to get from my house to this address either by using a smartphone or a website (because I have data or an internet connection), or by using my ability to read a map or consult a timetable. If I can do neither of these things, I would need to call a friend or a helpdesk. From the first step, and I haven't moved from home yet, there are many barriers to accessing information.

Once I have identified the starting point, I leave home. This assumes that the trip will be safe, whether I am a child, a disabled person, a senior citizen, or a woman, at any time of the day or night. I hope that I will be able to walk on the sidewalks and cross the streets and that I will not be assaulted on the way or while waiting for my bus.

I finally arrive at the starting point and I need to buy my ticket. I hope that someone will be able to help me if I don't know how to use my smartphone or the ATM, that I will understand the fare structure if I have to make a trip with several connections, and that they won't force me to buy an NFC card that I don't understand and that I will be able to pay with the method of payment that suits me.

I must still access the transportation mode, whether it be through a station, a platform, or a bus stop. Physical accessibility is an important issue here, and the experience of boarding and ticket validation is a potential source of frustration. Some services will not be accessible to all, such as those with bicycles or scooters, or old subway stations without access for disabled people. It is also important to consider that in some areas, for instance in rural areas, there is no or very little availability, whatever the mode of transport.

I arrive at my first stop, and need to see where I need to go to connect with the other line or the other transportation mode. I hope it will be easy to understand the place around me and to find my way through the station until my next destination. And so on.

Reading a map, finding one's way around the city, understanding a transportation network, using a smartphone application — all these require skills and they do not come naturally. There are many examples of young people who have never been out of their neighborhood or who live on the coast but have never seen the sea. For seniors, taking the bus means knowing how to use it: having a ticket, choosing the best route, knowing where the right stop is, finding your way around with a map and on the street, knowing the timetable, and not missing your stop. It’s a real survival mission. Mobility is, therefore, a learning process, at any age and for everyone. Reinforcing this learning process and supporting the professionalization of the social and professional integration support professions is essential.

Here are some keys to promoting inclusion in mobility solutions:

-

Democratize information accessibility on every support and every analogical and digital channel during every step of the customer journey.

-

Design accessible infrastructure for every capacity and transportation mode.

-

Guide people through public spaces with clear signage.

-

Offer payment methods aligned with every financial ability.

-

Define a system of decreasing prices according to resources and incomes, which facilitates the mobility of the poorest.

-

Ensure a safe environment inside and around stops, stations, and on board.

In the end, we need to resolve one burning issue: who will pay for that? Should private operators and companies lower their margins or should public authorities invest in it? In the end, it’s all about mission and values, culture and convictions. Do we want to build a better, more inclusive world that gives everyone an equal chance regardless of abilities? I would recommend driving local studies between associations, public authorities, and transport operators as the answer depends on the local socioeconomic reality.

Inclusive mobility is above all an approach that invites us to think about mobility from the point of view of uses and experiences and not only of travel. All mobility solutions must meet the needs of everyone, particularly people in situations of economic or social vulnerability. The objective is to give back their autonomy, by allowing everyone to have access to mobility. It is also an opportunity to develop local urbanism projects, to work on regional connectivity, and to promote equal opportunities.

By Olivier Bouvet | Transformation Experience Officer -

Wed, 06/21/2023 - 16:00

By Olivier Bouvet | Transformation Experience Officer -

Wed, 06/21/2023 - 16:00